The post Alien Antenna on Deep-Sea Floor first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>

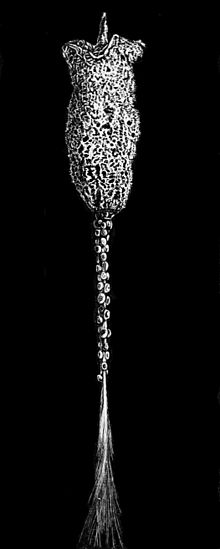

In 1964, the Antarctic oceanographic research ship USNS Eltanin made the above photograph of the sea bottom west of Cape Horn. The Poles: the final frontier. These were the voyages of the USNS Eltanin. Its 10-year mission: to explore strange new polar worlds. To seek out new life and survey new sealfoors. To boldly go where no man has gone before! Between July 5, 1962, and December 29, 1972, Eltanin conducted 52 Antarctic research voyages, covering approximately 80% of the Southern Ocean and traversing a cumulative distance of 400,000 miles. During these missions, Eltanin gathered magnetic profiles of the seabed, which played a crucial role in substantiating the theory of continental drift by confirming the phenomenon of sea floor spreading.

But back to the aliens. When the above image was published, due to its regular antenna-like structure and upright position led many to postulate was of extraterrestrial origins…an alien antenna

The initial public reveal of this intriguing image occurred when it grabbed attention in the New Zealand Herald on December 5, 1964, under the headline “Puzzle Picture From Sea Bed.” However, the enigma only deepened as additional layers unfolded. In 1968, Brad Steiger contributed to the intrigue with an article in Saga Magazine, suggesting that the Eltanin had captured something truly baffling—a curious apparatus resembling a fusion of a TV antenna and a telemetry antenna at with the height of 1.6 meters. Note there is no idea of scale in the original image so the height was pure conjecture. Various theories continue to circulate during that period, ranging from suggestions that it was a mere fragment that had accidentally dislodged from a vessel to more speculative notions, including the belief that it might be a clandestine endeavor of the Russians, or even more far-fetched hypotheses involving extraterrestrial involvement.

The biologist Dr. Thomas Hopkins, would say of “I wouldn’t like to say the thing is man-made because this brings up the problem of how one would get it there … But it’s fairly symmetrical and the offshoots are all 90 degrees apart”

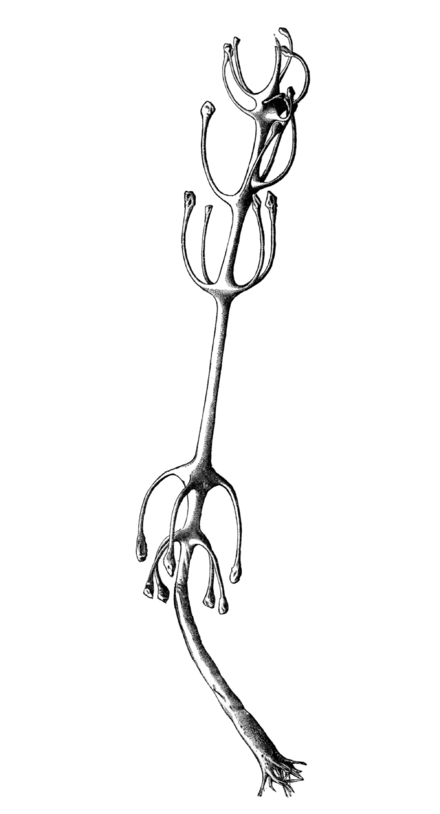

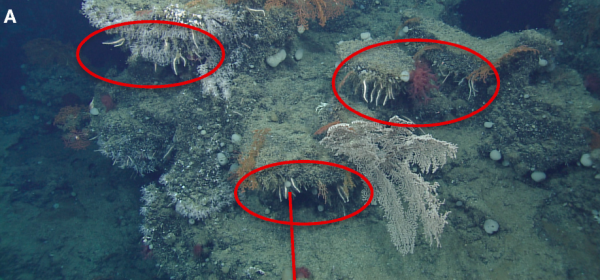

But apparently all these UFO enthusiasts had missed the 1971 book The Face of the Deep by Bruce C. Heezen and Charles D. Hollister. Hollister who had already identified the mysterious object as Cladorhiza concrescens, a carnivorous sponge. As pointed out by Heezen and Hollister, in 1888, Alexander Agassiz drew the odd creature in Three Cruises of the Blake. From 1877 to 1880, the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey dispatched the steamer Blake on three cruises of discovery—two expeditions to Florida, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Caribbean and one off the eastern Atlantic coast as far north as the Gulf of Maine. These cruises were designed to increase knowledge of the depths of the oceans and the animals and plants living on or near the bottom and to pioneer technological advances in oceanography You can access the entire Agassiz’s Three Cruises of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey steamer “Blake”, in the Gulf of Mexico, in the Caribbean Sea, and along the Atlantic coast of the United States, from 1877 to 1880 online. Agassiz described the strange sponge as having a long stem with ramifying roots deeply embedded in the mud, adorned with nodes bearing four to six club-like appendages, covering extensive portions of the seabed like bushes.

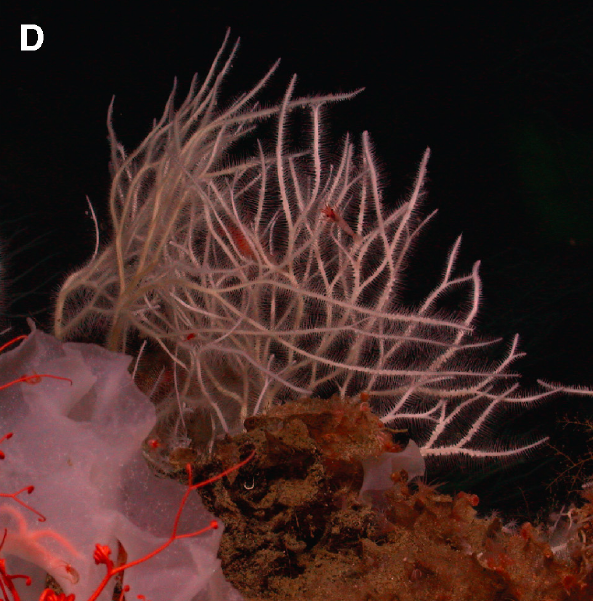

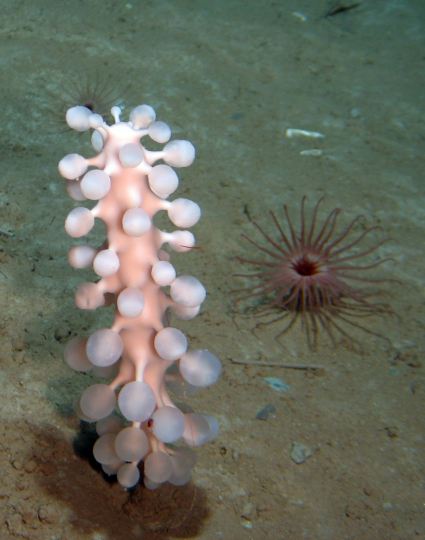

Below is screen grab from remote operated vehicles from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute from one of my dives of Cladorhiza concrescens on the seafloor. Indeed the Cladorhizid carnivorous sponges often have these very spectacular forms with 90 degree angles and intricate structures. I always refer to C. conscescens as the lollipop tree sponge.

However, this identification by Heezen and Hollister remained large ignored. In 2003, a discussion on email list prompted marine biologist Tom DeMary to reach out to A. F. Amos, an oceanographer who had been aboard the USNS Eltanin in the 1960s. Amos had know of the identification of the antenna as sponge and direct DeMary to the book by Heezen and Hollister. DeMary then shared this more broadly.

The post Alien Antenna on Deep-Sea Floor first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>The post The real-life cousins of SpongeBob first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>As much as we love SpongeBob at DSN, we—in a special committee formed to evaluate timely and societally important issues—have decided real sponges are much cooler.

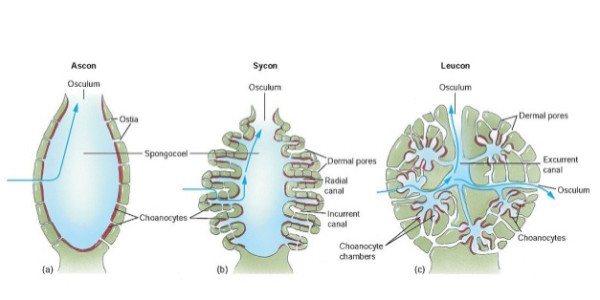

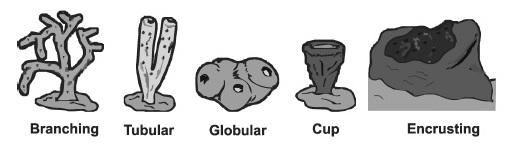

Sponges detest right angles. You know this already but let’s dive into the shape of sponges a little more. Hillenburg originally drew SpongeBob, then called Bob the Sponge, as a little more accurate amorphous blob. Sponge shapes do vary quite a bit but don’t include perfect right-angled boxes. One of the major differences is the presence of large internal chamber, called the spongocoel, and the degree of invagination or folding. In some cases, like the carnivorous Cladorhizids, the shapes become truly elegant. SpongeBob would be more biologically accurate if his name was SpongeBob VaseBottom.

Sponges detest right angles. You know this already but let’s dive into the shape of sponges a little more. Hillenburg originally drew SpongeBob, then called Bob the Sponge, as a little more accurate amorphous blob. Sponge shapes do vary quite a bit but don’t include perfect right-angled boxes. One of the major differences is the presence of large internal chamber, called the spongocoel, and the degree of invagination or folding. In some cases, like the carnivorous Cladorhizids, the shapes become truly elegant. SpongeBob would be more biologically accurate if his name was SpongeBob VaseBottom.

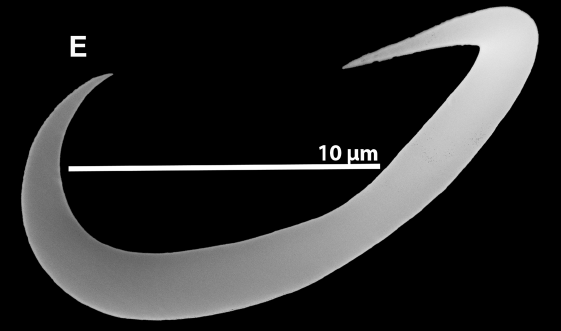

Sponges do not eat from a smorgasbord that includes bon-bons, bran flakes, cheeseburgers, or Rusty on Rye. The list of real and imaginary items that SpongeBob eats reaches the absurd. Real sponge diets are more mundane. Most sponges are filter-feeders eating bits of detritus…well..filtered out of the water. However, the deep-sea Cladorhizidae contain a unique type of spicule, the silica rods that serve as the scaffolding of sponges. The unique spicule of Cladorhizids is hooked that occur across the surface of the sponge like velcro. These can snag crustaceans that land or swim near the sponge. Once a crustacean is caught the sponge cells mobilize and digest the helpless victim. Imagine a mosquito lands on your arm to feed. The mosquito is caught in your long arm hairs. The insect is trapped unable to fly away. Within in short order, your epidermal cells mobilize growing a thin layer of skin over the mosquito. These cells slowly digest the mosquito providing you the nutrition to repeat the process again with the next unlucky flying insect.

Sponges do not eat from a smorgasbord that includes bon-bons, bran flakes, cheeseburgers, or Rusty on Rye. The list of real and imaginary items that SpongeBob eats reaches the absurd. Real sponge diets are more mundane. Most sponges are filter-feeders eating bits of detritus…well..filtered out of the water. However, the deep-sea Cladorhizidae contain a unique type of spicule, the silica rods that serve as the scaffolding of sponges. The unique spicule of Cladorhizids is hooked that occur across the surface of the sponge like velcro. These can snag crustaceans that land or swim near the sponge. Once a crustacean is caught the sponge cells mobilize and digest the helpless victim. Imagine a mosquito lands on your arm to feed. The mosquito is caught in your long arm hairs. The insect is trapped unable to fly away. Within in short order, your epidermal cells mobilize growing a thin layer of skin over the mosquito. These cells slowly digest the mosquito providing you the nutrition to repeat the process again with the next unlucky flying insect.

Sponges only come in the boneless variety. From the SpongeBob Wiki, “SpongeBob is usually shown to be boneless (sea sponges being invertebrates), however in some episodes such as “I Had an Accident,” bones are shown on his X-rays. He also had bones when he ripped his skin off in “Atlantis SquarePantis,” and “The Splinter.”” While real sponges do not have bones, they still have structure thanks to either silica or calcium carbonate skeletons, providing some real shape to an otherwise basically shapeless body. “Gary, I’m absorbing his blows like I’m made of some sort of spongy material”– Spongebob

Sponges only come in the boneless variety. From the SpongeBob Wiki, “SpongeBob is usually shown to be boneless (sea sponges being invertebrates), however in some episodes such as “I Had an Accident,” bones are shown on his X-rays. He also had bones when he ripped his skin off in “Atlantis SquarePantis,” and “The Splinter.”” While real sponges do not have bones, they still have structure thanks to either silica or calcium carbonate skeletons, providing some real shape to an otherwise basically shapeless body. “Gary, I’m absorbing his blows like I’m made of some sort of spongy material”– Spongebob

Sponges cannot carry a tune. From the SpongeBob Wiki, “SpongeBob is shown to possess a fantastic singing voice. He uses his nose as a flute, which he is very good. He was also the lead singer in “Band Geeks.” Later he uses his nose flute in “Best Day Ever” to drive away the Nematodes from the Krusty Krab.”” Real sponges communicate through chemical communication. A sponge can emit chemicals into the water that can be picked up by other sponges as they filter the water.

Sponges cannot carry a tune. From the SpongeBob Wiki, “SpongeBob is shown to possess a fantastic singing voice. He uses his nose as a flute, which he is very good. He was also the lead singer in “Band Geeks.” Later he uses his nose flute in “Best Day Ever” to drive away the Nematodes from the Krusty Krab.”” Real sponges communicate through chemical communication. A sponge can emit chemicals into the water that can be picked up by other sponges as they filter the water.

Sponges will not be winning Jeopardy. ”Can you give SpongeBob his brain back, I had to borrow it for the week”-Patrick. Unlike SpongeBob, real sponges lack brains and a nervous system. However, researchers from the University of California at Santa Barbara found that one species of sea sponge, called Amphimedon queenslandica, synthesizes many of the proteins that are essential for the cell-to-cell communication that takes place within nervous systems.

Sponges will not be winning Jeopardy. ”Can you give SpongeBob his brain back, I had to borrow it for the week”-Patrick. Unlike SpongeBob, real sponges lack brains and a nervous system. However, researchers from the University of California at Santa Barbara found that one species of sea sponge, called Amphimedon queenslandica, synthesizes many of the proteins that are essential for the cell-to-cell communication that takes place within nervous systems.

Sponge will never vote aye. Half of SpongeBob’s face is eyeballs. “Put those eyeballs back in your head, son!” –Policefish. Real sponges do not have eyes but sponge larvae are able to differentiate between different intensities of light, an ability that helps them find optimal locations to settle. Rings of light-sensitive cells contain special proteins, cryptochrome. However, these “eyespots” evolved independently of eyes and eyespots in other animals that use the protein opsin. This means the larval sponge “eyespots” evolved independently.

Sponge will never vote aye. Half of SpongeBob’s face is eyeballs. “Put those eyeballs back in your head, son!” –Policefish. Real sponges do not have eyes but sponge larvae are able to differentiate between different intensities of light, an ability that helps them find optimal locations to settle. Rings of light-sensitive cells contain special proteins, cryptochrome. However, these “eyespots” evolved independently of eyes and eyespots in other animals that use the protein opsin. This means the larval sponge “eyespots” evolved independently.

Real sponges are fulltime nudists. From the SpongeBob wiki, “Sometimes, SpongeBob is a nudist. In which he has a tendency to take off his clothes whenever he wants to. He was shown naked in “Ripped Pants,” “Nature Pants,” “The Paper,” “Hooky,” “Pranks a Lot,” “All That Glitters,” “Rise and Shine,” “Overbooked,” and “Model Sponge.”” Real sponges in nature are nudist all the time. Sediment and slime in the water can choke a sponge preventing it from filtering food and oxygen from the water. The sponge parts that are covered with sediment can quickly die.

Real sponges are fulltime nudists. From the SpongeBob wiki, “Sometimes, SpongeBob is a nudist. In which he has a tendency to take off his clothes whenever he wants to. He was shown naked in “Ripped Pants,” “Nature Pants,” “The Paper,” “Hooky,” “Pranks a Lot,” “All That Glitters,” “Rise and Shine,” “Overbooked,” and “Model Sponge.”” Real sponges in nature are nudist all the time. Sediment and slime in the water can choke a sponge preventing it from filtering food and oxygen from the water. The sponge parts that are covered with sediment can quickly die.

Real sponges do not keep snails as pet

Real sponges do not keep snails as pet s. Instead they parasitize them. SpongeBob has a pet snail, Gerald Wilson Jr. In real life, the boring sponges. A sponge larva will settle on a snail shell. As the sponge grows it chips off pieces of the shell and released into the water. As this continues, the sponge will form tunnels throughout the shell which eventually weakening the shell and killing the snail.

s. Instead they parasitize them. SpongeBob has a pet snail, Gerald Wilson Jr. In real life, the boring sponges. A sponge larva will settle on a snail shell. As the sponge grows it chips off pieces of the shell and released into the water. As this continues, the sponge will form tunnels throughout the shell which eventually weakening the shell and killing the snail.

The post The real-life cousins of SpongeBob first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>The post The Animals of the Musashi Battleship first appeared on Deep Sea News.

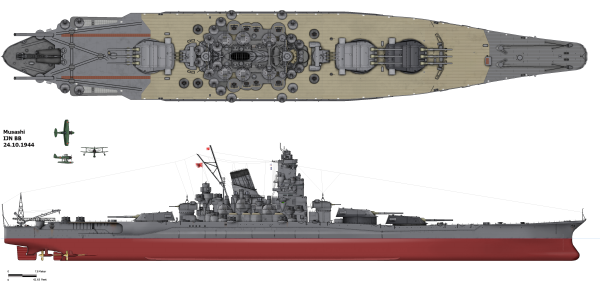

]]> On November 1st, 1940 the Imperial Japanese Navy launched the Yamato Class Battleship the Musashi. She and her sister ship, Yamato, were the heaviest and most powerfully armed battleships ever constructed. The Musashi was lost on October 24th 1944 during the Battle of Leyte Gulf during World War II. On March 2nd, an expedition lead by Microsoft cofounder, Paul Allen, found the Musashi at 1000m deep in the in the Sibuyan Sea. An exciting discovery but nonetheless I found the invertebrates inhabiting the wreck as equally interesting. Below, with the help of deep-sea invertebrate wiz Lonny Lundsten at MBARI, identify all the organisms seen in the video at the top.

On November 1st, 1940 the Imperial Japanese Navy launched the Yamato Class Battleship the Musashi. She and her sister ship, Yamato, were the heaviest and most powerfully armed battleships ever constructed. The Musashi was lost on October 24th 1944 during the Battle of Leyte Gulf during World War II. On March 2nd, an expedition lead by Microsoft cofounder, Paul Allen, found the Musashi at 1000m deep in the in the Sibuyan Sea. An exciting discovery but nonetheless I found the invertebrates inhabiting the wreck as equally interesting. Below, with the help of deep-sea invertebrate wiz Lonny Lundsten at MBARI, identify all the organisms seen in the video at the top.

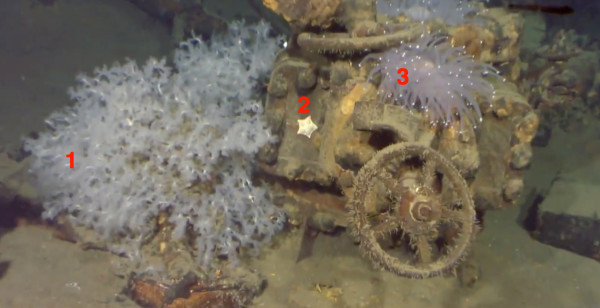

0:07-0:13 (1) Clathrina sp. of sponge, (2) Ceramaster sp. (cookie seastar), (3) Corallimorph anemone, and (4) a white squat lobster (Galatheidae) on the sponge

0:14-0:19 (5) White Hydroids growing on the valve wheel and (6) another squat lobster

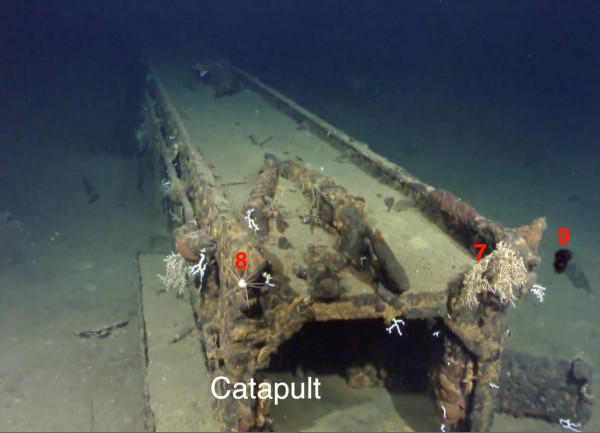

0:20-0:25 (7) a yellow Primnoidae or Plexauridae coral (just right of 7) white corals may be a species of Corallium (example 1, example 2), (8) a spikey urchin maybe Aspidodiadema, and (9) a swimmimg cucumber probably Enypniastes.

0:26-0:32 (10) a variety of small brittle stars

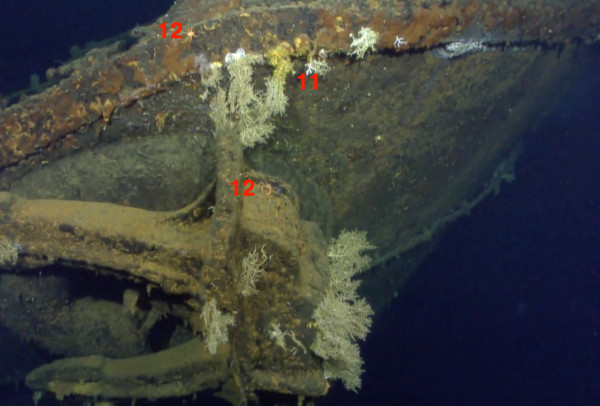

0:38-0:44 (11) Primnoidae or Plexauridae coral and (12) two orange Galatheidae squat lobsters

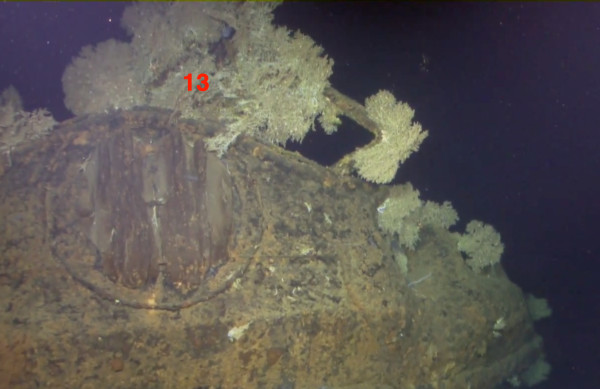

0:48-0:52 (13) Primnoidae or Plexauridae corals, but fouled with sediment or detritus and possibly dead

The post The Animals of the Musashi Battleship first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>The post These are a few of my favorite species: The magnificent and very large sponge Monorhaphis chuni first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>

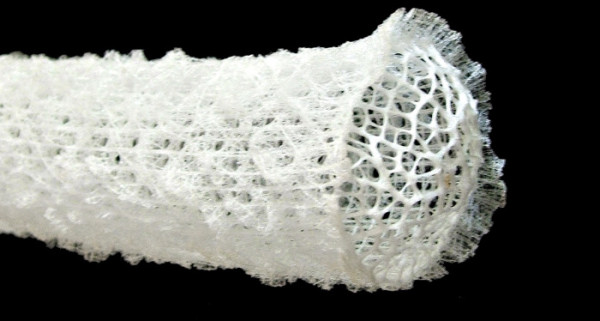

Within the glass sponges (Hexactinellids), so called because of scaffolds of silica spicules they form, resides a family of sponges, the Monorhaphididae. Family here is used in taxonomic sense to delineate substantially different types of organisms. Think the differences between cows and giraffes, both artiodactyls but in different families. But in the common meaning of the term family, Monorhaphididae has the saddest family of all—a family of one. The only species with this family is Monorhaphis chuni first described by by Franz Eilhard Schulze in 1904 from specimens collected by the German Deep Sea Expedition in 1898-1899. But despite this sponge’s lonely existence, it also dwells in the deep depths of the abyss, it lays claim to world record.

Monorhaphis chuni forms giant spicules that can reach 3 meters in length (~10 ft). These long spicules form the base of sponge putting the business end way up off the bottom to feed. Indeed lots of organism in the deep oceans are stalked or climb atop other stalked organisms to feed in the water off the bottom. Currents very near the bottom are sluggish because of friction of the water against the seafloor. Getting up into the water column gives an animal access to stronger currents carrying both oxygen and particles of food.

Monorhaphis chuni forms giant spicules that can reach 3 meters in length (~10 ft). These long spicules form the base of sponge putting the business end way up off the bottom to feed. Indeed lots of organism in the deep oceans are stalked or climb atop other stalked organisms to feed in the water off the bottom. Currents very near the bottom are sluggish because of friction of the water against the seafloor. Getting up into the water column gives an animal access to stronger currents carrying both oxygen and particles of food.

But back to that gargantuan spicule! That big bastard represents the largest silica structure on Earth made by an animal. To make that magnificent piece of glass takes awhile though. Researchers found that the one particularly long spicule dated to 11,000 ± 3000 years old

Jochum, Klaus Peter, Xiaohong Wang, Torsten W Vennemann, Bärbel Sinha, and Werner E G Müller. 2012. “Siliceous Deep-Sea Sponge Monorhaphis Chuni: a Potential Paleoclimate Archive in Ancient Animals.” Chemical Geology 300-301: 143–51. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2012.01.009.

The post These are a few of my favorite species: The magnificent and very large sponge Monorhaphis chuni first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>The post These Are a Few of My Favorite Species: Carnivorous Sponges first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>

Flagellum and ingesting puppies, metaphorically speaking, is the norm for most sponges. However, in the dark depths of oceans and in the black caverns of the marine caves, lurks Earth’s strangest creatures—the carnivorous sponges.

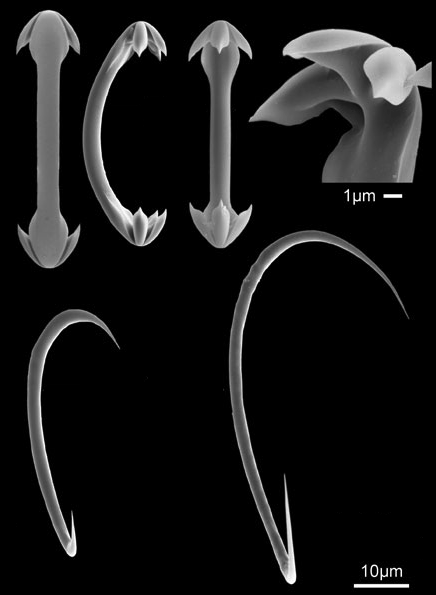

Most sponges are composed of spicules, little shards of silica, that provide structure. In the carnivorous sponges, Cladorhizidae, some spicules are shaped like hooks. Unsuspecting tiny crustaceans or other animals near the sponge are often caught in the sheets of hooks that line the surface of the Cladorhizid sponges, much schmutz in Velcro. In some Cladorhizids copepods may be caught by an adhesive surface. Once a crustacean is caught, the cells surrounding mobilize, cover, and create a temporary cavity around the crustacean. Within this cavity the crustacean is digested. It’s the equivalent of mosquito being caught in your arm hairs, the skins cells then form a layer of skin over it, and finally you digest the mosquito just below the surface of the skin.

The post These Are a Few of My Favorite Species: Carnivorous Sponges first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>The post What is the world's largest barrel sponge? first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]> It is probably this 2.5 meter (8.2 feet) diameter giant that was a tourist attraction for scuba divers visiting Curaçao in the Caribbean in the early 1990s. Unfortunately frequent touching by scuba divers likely caused lesions that lead to an infection of the sponge tissue (show as the dark spot pointed to by the arrow in the photo). By mid-May of 1997 only a large piece of the outer edge sponge remained. Other barrel sponges in the area were were not impacted suggesting that it was indeed the touching by divers that led to the sponge’s demise. Through the research of my student Shane Stone and myself, this specimen is so far the largest documented specimen.

It is probably this 2.5 meter (8.2 feet) diameter giant that was a tourist attraction for scuba divers visiting Curaçao in the Caribbean in the early 1990s. Unfortunately frequent touching by scuba divers likely caused lesions that lead to an infection of the sponge tissue (show as the dark spot pointed to by the arrow in the photo). By mid-May of 1997 only a large piece of the outer edge sponge remained. Other barrel sponges in the area were were not impacted suggesting that it was indeed the touching by divers that led to the sponge’s demise. Through the research of my student Shane Stone and myself, this specimen is so far the largest documented specimen.

Nagelkerken, I. 2000 Barrel sponge bows out. Reef Encounter 28, 14-15.

The post What is the world's largest barrel sponge? first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>The post Velcro, romance, and consuming the flesh of crustaceans first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>Imagine a mosquito lands on your arm to feed. The mosquito is caught in your long arm hairs. The insect is trapped unable to fly away. Within in short order, your epidermal cells mobilize growing a thin layer of skin over the mosquito. These cells slowly digest mosquito providing you the nutrition to repeat the process again with the next unlucky flying insect.

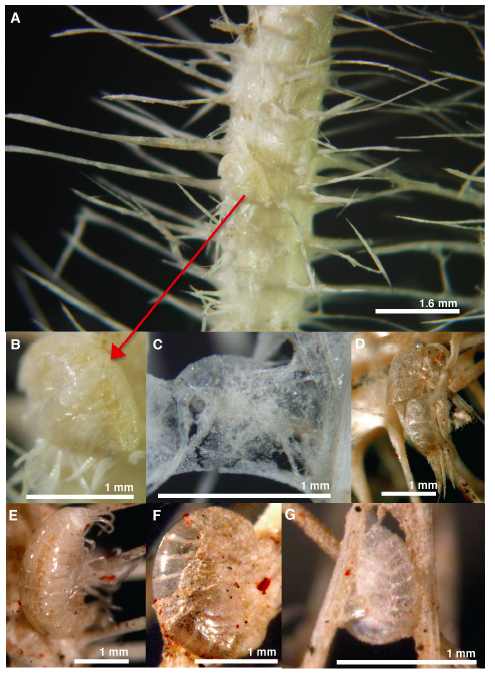

My favorite sponges, in the group Cladorhizidae, feed almost exactly like this. In a recent paper, my friend and colleague Lonny Lundsten from the Monterey Bay Aquarium describes four new species of these unique sponges. The first is Abestopluma monticola, the scientific name referring to where it was first discovered, a seamount (Latin mont = mountain + -cola = dweller).

The second is Asbestopluma rickettsi named for the famous intertidal ecologist Ed Ricketts, made famous by John Steinbeck.

The third is Cladorhiza caillieti named for Gregor M. Cailliet, Professor Emeritus at Moss Landing Marine Laboratories a well respected ichthyologist and deep-sea biologist.

But the last name and the reasoning behind is the one that moves me most, Cladorhiza evae. In Lonny’s own words

Named in honor of Eve Lundsten, beautiful wife of the first author whose commitment and support have endured through the years. Eve’s love for the Gulf of California also inspired this naming as the type specimen was collected.

What sets the species of the deep-sea Cladorhizidae apart is a unique type of spicule, the silica rods that serve as the scaffolding of sponges. This unique spicule of Cladorhizids is hooked. These spicules occur across the surface of the sponge like velcro. These can snag crustaceans that land or swim near the sponge. Once a crustacean is caught the cells mobilize and…well you know the rest of the story. What makes Lonny’s paper unique, other than describing four new species that is, is the inclusion of set of spectacular plates that actually show crustaceans caught and covered in a layer of sponge cells. This behavior is also unique among sponges as most are perfectly content filtering particles out of the water and not consuming living flesh of nearby crustaceans.

What sets the species of the deep-sea Cladorhizidae apart is a unique type of spicule, the silica rods that serve as the scaffolding of sponges. This unique spicule of Cladorhizids is hooked. These spicules occur across the surface of the sponge like velcro. These can snag crustaceans that land or swim near the sponge. Once a crustacean is caught the cells mobilize and…well you know the rest of the story. What makes Lonny’s paper unique, other than describing four new species that is, is the inclusion of set of spectacular plates that actually show crustaceans caught and covered in a layer of sponge cells. This behavior is also unique among sponges as most are perfectly content filtering particles out of the water and not consuming living flesh of nearby crustaceans.

LUNDSTEN, L., REISWIG, H., & AUSTIN, W. (2014). Four new species of Cladorhizidae (Porifera, Demospongiae, Poecilosclerida) from the Northeast Pacific Zootaxa, 3786 (2) DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.3786.2.1

LUNDSTEN, L., REISWIG, H., & AUSTIN, W. (2014). Four new species of Cladorhizidae (Porifera, Demospongiae, Poecilosclerida) from the Northeast Pacific Zootaxa, 3786 (2) DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.3786.2.1

The post Velcro, romance, and consuming the flesh of crustaceans first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>The post Amazing close-up video of Great Barrier Reef animals first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>Daniel Stoupin’s message is simple: Please care for the Great Barrier Reef. His film, on the other hand, shows the incredible complexity of the animals that live there. This video has left me completely in awe.

Below, I’ve tried to provide information of the animals featured in the video. In some cases, I don’t know. For specific IDs I’ve looked to Daniel’s website for help. Daniel was also kind enough to check them for me. That being said, there are still some unknowns. I encourage others to chime in with more information in the comment section. I’ll update this post as new information becomes available.

As for the vivid colors, Daniel uses full spectrum light (shifted to the blue) to bring out the animal’s natural fluorescence. Beautiful.

0:01-0:15 — the stunning crown of a filter-feeding annelid worm. Worms like this live in tubes or burrows, with only their delicate feeding structures exposed. Once a food particle is ensnared, cellular hairs guide it to the central mouth. *Update* According to Smithsonian zoologist Allen G. Collins, it’s probably a sabellid.

0:01-0:15 — the stunning crown of a filter-feeding annelid worm. Worms like this live in tubes or burrows, with only their delicate feeding structures exposed. Once a food particle is ensnared, cellular hairs guide it to the central mouth. *Update* According to Smithsonian zoologist Allen G. Collins, it’s probably a sabellid.

0:22-0:45 — a soft coral colony. Known as “octocorals”, soft corals are different from the more familiar hard corals in that they don’t have a hard skeleton. Instead, they use a complex mesh of biomolecules to shape the colony. Soft coral polyps also have 8 tentacles, hence the name “octocoral.” *Update* Allen G. Collins thinks this is a Heteroxenia.

0:22-0:45 — a soft coral colony. Known as “octocorals”, soft corals are different from the more familiar hard corals in that they don’t have a hard skeleton. Instead, they use a complex mesh of biomolecules to shape the colony. Soft coral polyps also have 8 tentacles, hence the name “octocoral.” *Update* Allen G. Collins thinks this is a Heteroxenia.

0:46-0:55 — This is a close-up of a mushroom coral (Discosoma sp). This looks like a solitary species. Solitary corals are, well, exactly that, single coral polyps that live alone, not as part of a colony. They can be quite large, I often see solitary corals about the size of a human hand. *Update* Allen G. Collins suggests this may be a corallimorph, a relative of corals.

0:46-0:55 — This is a close-up of a mushroom coral (Discosoma sp). This looks like a solitary species. Solitary corals are, well, exactly that, single coral polyps that live alone, not as part of a colony. They can be quite large, I often see solitary corals about the size of a human hand. *Update* Allen G. Collins suggests this may be a corallimorph, a relative of corals.

0:56-1:01 — Favites pentagona, known by the shamelessly amusing common name of “red and green war coral”.

0:56-1:01 — Favites pentagona, known by the shamelessly amusing common name of “red and green war coral”.

1:01-1:04 — This is a species of hermaphroditic cup coral, called Acanthastrea lordhowensis.

1:01-1:04 — This is a species of hermaphroditic cup coral, called Acanthastrea lordhowensis.

1:05-1:20 — A polyp digging its way out of sediment. Amazing! I think this is, again, a solitary coral polyp.

1:05-1:20 — A polyp digging its way out of sediment. Amazing! I think this is, again, a solitary coral polyp.

1:20-1:35 — no idea, but I want one.

1:20-1:35 — no idea, but I want one.

1:41-1:51 — A little coral polyp opening up at night. According to Daniel it’s the same species as above.

1:41-1:51 — A little coral polyp opening up at night. According to Daniel it’s the same species as above.

1:52-2:02:01 — DEAR GAWD! Is that the excurrent canal of a sponge?! I can’t think of what else it would be, but at the same time I kinda don’t believe it. Sponges (those animals that look like rocks and gave us the dish sponge) have a network of tiny pores along their surface. These pores suck in water and the animal then filters out food particles. All the water eventually leaves the sponge through a large opening, or excurrent canal. But….I had no idea they moved…

2:02-2:26 — ok, all these look like sponges, but I’m still finding it hard to believe. *Update* Yep, they’re sponges. According to Daniel, “Sponges regulate water flow by means of adjusting the diameter of their canals (in addition to speed of flagella beating). You can actually see individual cells working to make the seal.”

2:02-2:26 — ok, all these look like sponges, but I’m still finding it hard to believe. *Update* Yep, they’re sponges. According to Daniel, “Sponges regulate water flow by means of adjusting the diameter of their canals (in addition to speed of flagella beating). You can actually see individual cells working to make the seal.”

2:27-2:33 — little coral polyps. According to Daniel it’s a Goniopora.

2:27-2:33 — little coral polyps. According to Daniel it’s a Goniopora.

2:34-2:38 — I’m blown away by all the colors here. The fluorescence is really incredible. More Acanthastrea lordhowensis polyps (starry cup coral).

2:34-2:38 — I’m blown away by all the colors here. The fluorescence is really incredible. More Acanthastrea lordhowensis polyps (starry cup coral).

2:38-2:44 — According to Daniel, it’s a Favia.

2:38-2:44 — According to Daniel, it’s a Favia.

2:45-2:52 — A “rainbow Lobophyllia.” Seems like a good name…

2:45-2:52 — A “rainbow Lobophyllia.” Seems like a good name…

2:53-3:00 — A purple zoanthid colony. Zoanthids are similar to corals, widely distributed, and popular with photographers and aquarists. Surprisingly, from a scientific perspective, we know very little about them.

2:53-3:00 — A purple zoanthid colony. Zoanthids are similar to corals, widely distributed, and popular with photographers and aquarists. Surprisingly, from a scientific perspective, we know very little about them.

3:00-3:02 — hard coral polyps of some kind. *Update* According to commenter Dr_Yak, it may be a Platygyra.

3:00-3:02 — hard coral polyps of some kind. *Update* According to commenter Dr_Yak, it may be a Platygyra.

3:12 — more soft corals, known as octocorals.

3:12 — more soft corals, known as octocorals.

3:13-3:19 — A sea urchin! The yellow structures are spines. The brown worm-like structures with white tips are tube feet. Urchins use tube feet to move around, stick to things, and even sense light! The little blue structures are called pedicellariae. Pedicellariae are like little claws the urchin uses to grab onto rocks or fend off invaders. In some species they can be venomous.

3:13-3:19 — A sea urchin! The yellow structures are spines. The brown worm-like structures with white tips are tube feet. Urchins use tube feet to move around, stick to things, and even sense light! The little blue structures are called pedicellariae. Pedicellariae are like little claws the urchin uses to grab onto rocks or fend off invaders. In some species they can be venomous.

And now I’m going to watch it again. And again. And again.

For more amazing images and video, check out Daniel’s website: MicroWorldsPhotography.com

The post Amazing close-up video of Great Barrier Reef animals first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>The post Fossil Carnivorous Sponge? first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>

And here is a contemporary and Cladorhizid species.

The post Fossil Carnivorous Sponge? first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>The post Flesh Eating Sponges? first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>Flagellum and ingesting puppies, metaphorically speaking, is the norm for most sponges. However, in the dark depths of oceans and in the black caverns of the marine caves, lurks Earth’s strangest creatures—the carnivorous sponges.

Most sponges are composed of spicules, little shards of silica, that provide structure. In the carnivorous sponges, Cladorhizidae, some spicules are shaped like hooks. Unsuspecting tiny crustaceans or other animals near the sponge are often caught in the sheets of hooks that line the surface of the Cladorhizid sponges, much schmutz in Velcro. In some Cladorhizids copepods may be caught by an adhesive surface. Once a crustacean is caught, the cells surrounding mobilize, cover, and create a temporary cavity around the crustacean. Within this cavity the crustacean is digested. It’s the equivalent of mosquito being caught in your arm hairs , the skins cells then form a layer of skin over it, and finally you digest the mosquito just below the surface of the skin.

The first species of Cladorhizid was described only recently in 1995 from submarine caves in the Mediterranean. In approximately the last 20 years, 33 species have been discovered and described, with several more in the works. Even though new to humans, Cladorhizids have dwelled on Earth since at least the Pleistocene, 2 million years ago. Fossils from this period are easily identifiable as the bizarre sponges. However, 200 million year old spicules do bear a striking resemblance to those from the carnivorous sponges of the modern oceans.

Even more unusual is the bewildering shapes that Cladorhizids take, from the pipe cleaner structure of Abestopluma, to the ping pong tree structure of Chondrocladia lampadiglobus, to the beautiful harp shape of Chondrocladia lyra. The evolutionary reasons for this vast variety of shapes among species remains a major unknown, as is most of the biology of the fascinating group. Despite our lack of knowledge a carnivorous sponge is deserving of rightful place as a top 10 species.

Les Watling (2007). Predation on copepods by an Alaskan cladorhizid sponge. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, pp 1721-1726. doi:10.1017/S0025315407058560.

Vacelet, Jean & Boury-Esnault, N. (1995): Carnivorous sponges. Nature 373 (6512): 333–335. doi:10.1038/373333a0

Lee, W. L., Reiswig, H. M., Austin, W. C. and Lundsten, L. (2012), An extraordinary new carnivorous sponge, Chondrocladia lyra, in the new subgenus Symmetrocladia (Demospongiae, Cladorhizidae), from off of northern California, USA. Invertebrate Biology. doi: 10.1111/ivb.12001

The post Flesh Eating Sponges? first appeared on Deep Sea News.

]]>